Year 1700-1799 AD

-

1750: David Hume publishes essay on the causes of observed climatic change

-

1700-1750: Rostocker Harbour closed by sand on Falster, Denmark

-

1772: Vernagtferner in Austria advances again into Rofental and ice dammed Rofener Eissee reforms

-

1786: Observations on glacier size in Lituya Bay, south-eastern Alaska

1709:

The year that Europe froze solid ![]()

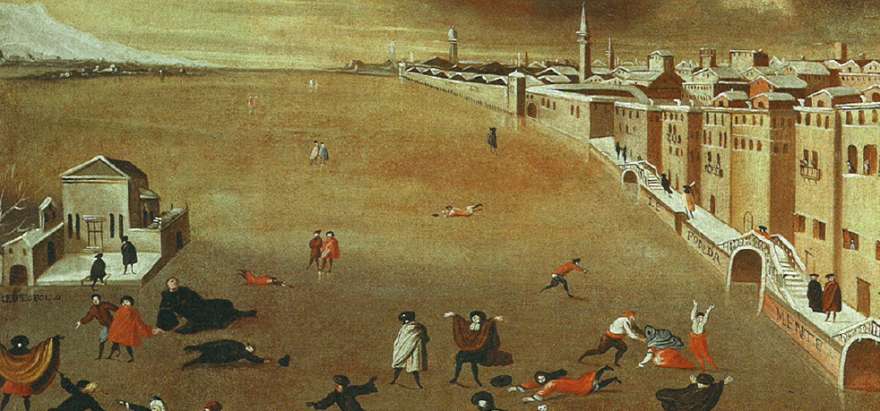

The Venetian lagoon frozen over in 1709.

Early January 1709 temperatures were dropping over most of Europe (Pain 2009). The cold remained for three weeks, and was followed by a brief thaw. Then temperatures plunged again and stayed there. From Scandinavia in the north to Italy in the south, lakes, rivers and even the sea froze. At Upminster, shortly north-east of London, temperature fell to -12oC on 10 January 1709, while it sank to -15oC in Paris on 14 January, and stayed at that level for the next 11 days. It has been estimated that the winter air temperature in Europe was as much as 7oC below the average for 20th century Europe. Not only was January very cold, it also turned out to be unusually stormy (Pain 2009).

In England the winter of 1709 became known as the Great Frost, while it in France entered the legend as Le Grand Hiver (Pain 2009). In France, even the king and his courtiers at the Palace of Versailles struggled to keep warm. In Scandinavia the Baltic froze so thoroughly that people could walk across the sea as late as April 1709. In Switzerland hungry wolves became a problem in villages. Venetians were able to skid across the frozen lagoon (see painting above).

According to a canon from Beaune in Burgundy, "travellers died in the countryside, livestock in the stables, wild animals in the woods; nearly all birds died, wine froze in barrels and public fires were lit to warm the poor". From all over the country came reports of people found frozen to death. Roads and rivers were blocked by snow and ice, and transport of supplies to the cities became difficult. Paris waited three months for fresh supplies (Pain 2009).

In Russia, the intense cold contributed significantly to the defeat of the Swedish army at Poltava under King Karl XII. Poltava became a political turning point for both Sweden and Russia: Sweden never regained its former military might, while Russia began to emerge as a European superpower (see text below).

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1709:

Swedish defeat at Poltava![]()

In

1697 the Swedish king Karl XII

(1682-1718) assumed the crown at the age of fifteen, at the death of his father.

As king, he embarked on a series of battles overseas. In 1700, Denmark-Norway,

Having

first defeated Denmark-Norway in 1700, King Karl

turned his attention upon the two other powerful neighbours,

In

the meantime, Tsar Peter had embarked on a military reform plan to improve the

quality of the Russian army. Especially the development of the artillery was

emphasised. In the last days of 1707 King Karl crossed the frozen

The

Russian tactical plan was to avoid a decisive battle before the Swedish army had

been weakened by the progress of time. When hostilities were resumed in June 1708 the Russian army

therefore slowly retreated towards

King

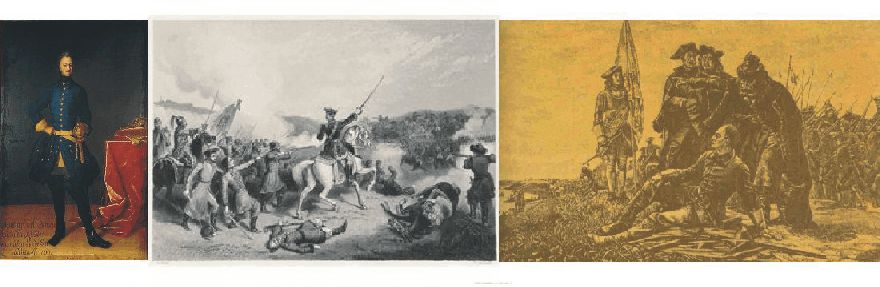

Karl XII of Sweden (left). Battle of Poltava (centre). King Karl at the Dnieper

River during the catastrophic retreat following the battle of Poltava.

The

extremely low temperatures characterizing the winter 1708-1709 had taken their

toll on the Swedish soldiers. When the Swedish army finally began its siege of

Poltava 1 May 1709, Karl has lost most of his army without any big battles being

fought. In June Tsar Peter began concentrating an army shortly north of Poltava.

Karl had to face this treat, but following the hard winter he was only able to muster about 12,000

men for the attack. The attack was launched 28 June 1709, but was affected by

some tactical confusion on the Swedish side. After some initial

successes, the Swedish army was defeated thoroughly by the much larger Russian

army, mainly due to its numerical superiority, and partly because of the now

very strong and efficient Russian artillery.

By this, the battle at Poltava represented a climatic induced turning point for both Sweden and Russia. Sweden never regained its former military might, while Russia was beginning to emerge as a European superpower.

King

Karl XII himself managed to escape with 1,200 Swedish survivors to the northerly

province of the

1719:

The Aurora Borealis observed in New England ![]()

Aurora Borealis. Oil on canvas. Part of painting by Frederic Edwin Church. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

In 1891 Sidney Perley published a book entitled Historical Storms of New England, graphically describing every major storm and natural disaster in New England from 1635 to 1890. In 2001 the whole book was reprinted due to widespread interest (Perley 2001). It is interesting to note, that Perley (2001) within his chosen context feels it natural to incorporate the first observation of northern lights in New England.

He states (p 31-33) the following: "The northern lights, as they are called, first attracted the attention of the people of New England in March, 1718, and there was a general fear that dire calamities would result therefrom. May 15, 1719, the more beautiful and brilliant aurora borealis was first observed here as far as any record or tradition of that period inform us, and it is said that in England it was first noticed only three years before this date. In December of the same year the aurora again appeared, and the people became greatly alarmed, not dreading it so much as a means of destruction but as precursor of the fires of the last great day and a sign of coming dangers."

"Though at first the people were fearful for the consequences of such sights, the feeling wore off as they became more frequent and it was found that they were without any apparent effect upon the world. They have now (1891) become sights of curiosity merely to most people, who, while they cannot fully explain them, know that they portend no evil; though many have ever since those early times been more or less concerned when any strange cloud appears."

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1728:

The Inuit invasion of Scotland ![]()

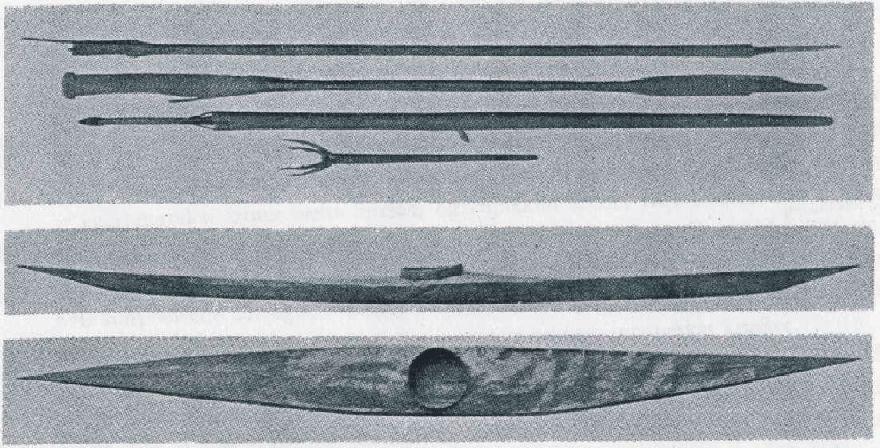

The

Inuit kayak that in 1728 appeared at the coast of eastern Scotland, near

In

the year 1728 a strange vision appeared on the sea near

There

are many indications of the existence of an enhanced thermal high pressure over

the Greenland Ice Sheet during the Little Ice Age. Presumably, northerly and

north-westerly winds along

It has been suggested that this

Inuit with his kayak was kidnapped by European whalers and brought across the

Whatever is the correct

explanation for these extraordinary events, all known Inuit landings in

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1728:

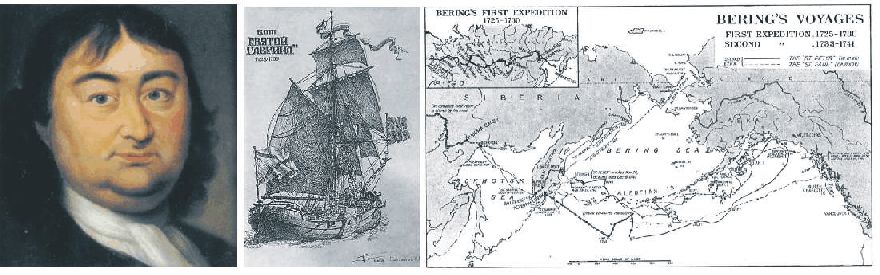

Vitus Bering and the non-discovery of Bering Strait ![]()

Vitus Jonassen Bering (left). The ship Svyator Gavriil under sail (centre). Map showing Bering's expeditions between Sibiria and Alaska (right). The 1728 expedition followed the coast of Kanchatka towards NW Alaska.

Tsar

Peter I the Great (1692-1725) has always been fascinated by geographical

problems, especially the possibility of a Northern Sea Route along Russioa’s

Arctic coast, and the related question of whether there was a strait separating the continents of Asia and America.

Unfortunately, he was usually to busy

fighting his neighbours and modernizing Russia to pay much attention to the

eastern part of his huge empire.

In

1724 the Danish navigator Vitus Jonassen Bering ( 1681-1741) was ordered to

organize an expedition to sail along the coast north from Kamchatka, and explore

and map the area where that coast came nearest to America. Vitus Bering was 43

years old and had been in the service of the Russian Navy since 1703, where he

actually was better known as Ivan Ivanovich. Bering was a gifted administrator

and rapidly organized the expedition, which involved transport of 30 men and 50 wagons

of baggage and equipment overland for mostly road less 8,000 km from St.

Petersburg to the Sea of Okhotsk, and on to the east coast of Kamchatka. In the

Kamchatka River the expedition ship Svyator Gavriil had to be build.

The expedition left on 13 July 1728, and sailed up along the coast in northeasterly direction. In bad visibility they sailed through the strait which James Cook 50 years later named after Beiring. The expedition proceeded northeast without seeing land. On 13 August, when Svyator Gavriil was at 65o30’N, Bering called the council of the ship’s officers to decide what to do. It was agreed to proceed for three more days to see if land or solid sea ice was met. Neither land or sea ice was met, and the expedition turned back shortly beyond 67oN on 16 August 1728. Had Vitus Bering been a more determined explorer and therefore pressed on in the ice-free ocean, the expedition would shortly after have made landfall near the settlement Kivalina. At Kivalina the inhabitants on 27 February 2008 complained on the lack of sea ice because of by man-made global warming.

By this, Bering has shown himself

to be an excellent administrator and navigator, but not a resolute explorer. No

wonder Bering’s reception on his return to

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1740-1741:

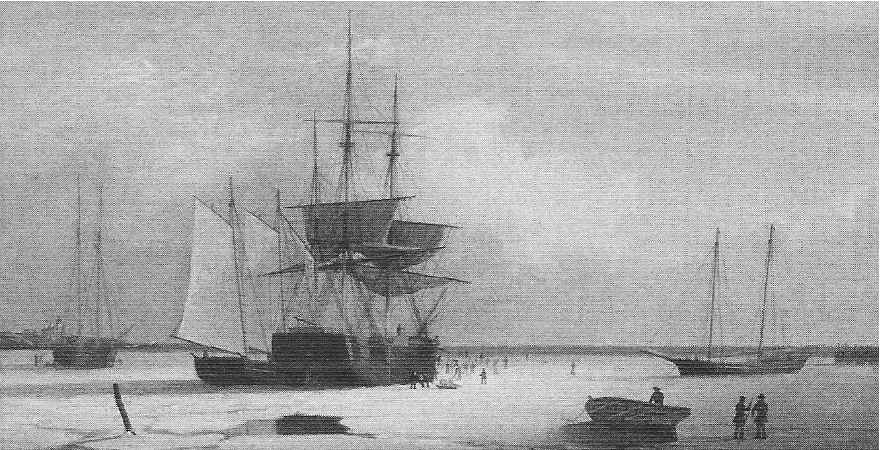

A very cold winter in New England ![]()

Ships frozen inn near Ten Pound Island northeast of Boston, Massachusetts. Grey reproduction of part of oil painting on canvas by Fitz Hugh Lane. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The summer of 1740 was cold and wet in New England (Perley 2001). Early frost injured much of the corn crop, and ripening was inhibited by a long period of rain. About one-third of the corn was cut when still green, and the rest was so wet that it soon was destroyed. Only little seed corn was available in New England for the next spring's planting, and the amount of dry corn for winter consumption was small as well. In addition, the rainy summer and fall 1740 resulted in widespread flooding of the lowlands.

The winter 1740-1741 began early. The rivers of Salem, Massachusetts, were frozen over as early as October, and on 4 November air temperatures became very low (Perley 2001). Snow was falling, and measured a foot in depth on 15 November in Essex Country, Massachusetts. On 22 November the weather became warmer, and it rained for nearly three weeks. The snow melted, and the Merrimack River flooded its surroundings. At Haverhill, the river rose about 5 metres.

The the cold then came back, and both the Plum Island River and the Merrimack River was again frozen over from around mid-December, until the end of March. The cold became severe, and soon the river ice was able to carry the weight of loaded sledges drawn by horses. As far south as New York, the harbours were closed by ice, and ships remained frozen in for long time (Perley 2001).

Not only was the winter 1740-1741 characterised by very low temperatures, but also by huge amounts of snow. People in the region saw this winter as the most severe since the European settlement began. There was 23 snow storms in all, most of them being strong. On 3 February about a foot of snow fell, and about one week later there were two more storms, filling the roads in Newbury, Massachusetts, up to the top of fences. Snow depths of about 3 metres were reported from some places.

The snow remained on the ground into April and May 1741, delaying the time when the ground was ready for planting. The farmers were almost discouraged, thinking of the failure of the corn crop the year before (Perley 2001).

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1742:

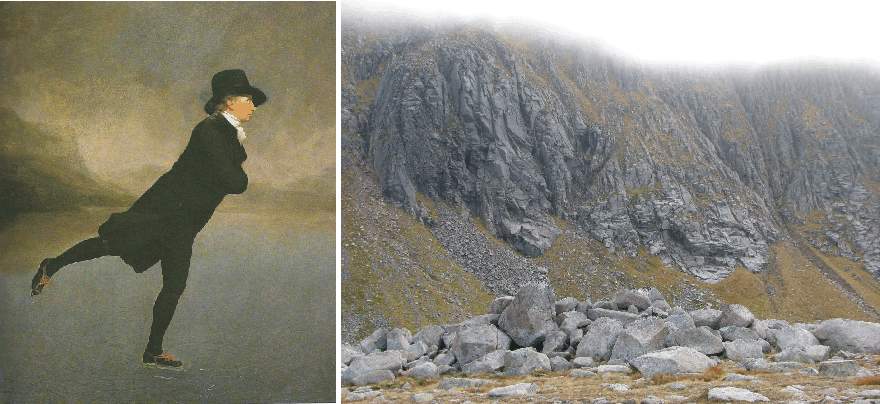

The world's first skating club formed in Edinburgh ![]()

The skating minister. Sir Henry Raeburn's painting of the Rev. Dr. Robert Walker skating on Duddingston Loch (left; c. 1795). Younger Dryas moraine in CoireAnT-Sneachda, Cairngorm mountains, eastern Scotland, October 7, 2007 (right). This moraine was once speculated to have formed during the Little Ice Age by a small glacier. Later investigations, however, demonstrated that there has been no glaciers in Scotland since the Younger Dryas period (c. 13,000-11,500 years before now).

The Little Ice Age (c. 1300-1915) is known as a period of climatic deterioration in Scotland, including the coldest conditions since the end of the last glaciation. Severe snowy winters, storms, heavy rainfall and summer droughts characterise this period with records of flooding, shipwrecks, loss of life and livestock, and famines (McKirdy et al. 2007). Click here and here to se two examples of this.

The late seventeenth century was particular cold and a time of great hardship in Scotland. However, there was also benefits for some; for example, the world's first skating club was formed in Edinburgh in 1742. As a test for admission, aspiring members had to jump successfully over three hats and perform a circle while skating on one foot. As captured in Sir Henry Raeburn's painting (above), the Rev. Dr Robert Walker skating gracefully on Duddingston Loch would surely have passed (cf. McKirdy et al. 2007).

The 20th warming following the Little Ice Age resulted in frozen lakes around Edinburgh being rare or absent in most years.

North of Edinburgh, in the Caringorms, travellers noted late-lying snow in the mountains, and it is likely that there were many more snowbeds surviving throughout the year than today. Snow may even have covered the high Cairngorm plateau for decades at a time (McKirdy et al. 2007). John Taylor (1618) noted: "I saw Mount Benawne [today: Ben Avon], with a furr'd mist upon his snowie head instead of a nightcap, (for you must understand, that the oldest man alive never saw but the snow was on top of divers of those hilles, both in Summer, as well as in Winter)." Later Thomas Pennant (1769) described a contemporary view of the hills from Deeside, as follows: "naked summits of a surprising height succeed, many of them topped with perpetual snow." The Rev Charles M'Hardy (1793), referring to the Cairngorm mountains Lochnagar, Bein a'Bhuird and Ben Macdui, wrote that: "Upon these mountains, and others connected with them, there is snow to be found all the year round; and their appearance is extremely romantic, and truly alpine."

The 20th warming following the Little Ice Age resulted in an widespread loss of surviving snowbeds in Scotland. Some years no snow at all survived the summer in the Scottish mountains. This is known to be the case in the years of 1933, 1959, 1996 and 2003 (McKirdy et al. 2007).

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1747-1748:

A memorable winter in Massachusetts ![]()

In 1891 Sidney Perley (Perley 2001) writes: "The old people of to-day think that we do not have as severe winters as they had when they were in their youth, and they certainly have good reasons for such considerations. The winter of 1747-48 was one of the memorable winters that used to be talked about by our grandfathers when the snow whirled above deep drifts around their half-buried houses. There were about thirty snow storms, and they came storm after storm until the snow lay four feet deep on the level, making travelling exceedingly difficult. On the twenty-second of February, snow in the woods measured four and one-half feet; and on the twenty-ninth there was no getting about except on snow shoes".

Apparently, at the time of Perley's writing (in 1891) the general notion in New England was that of some climatic improvement (warming), compared to conditions prevailing previously in this region of North America.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

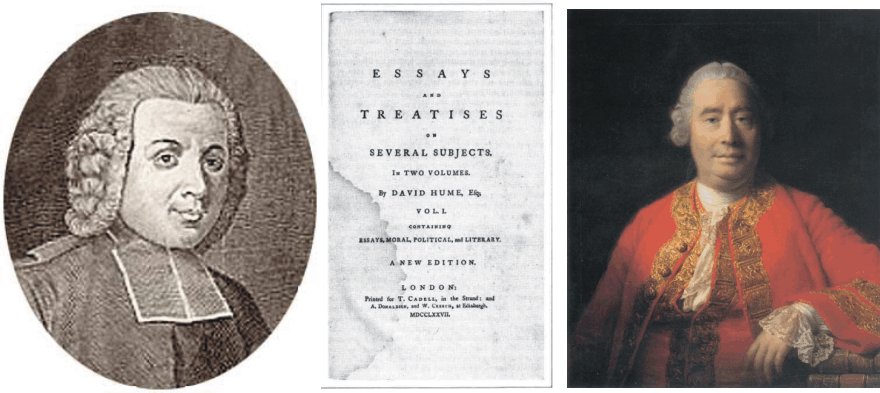

1750:

David Hume publishes essay on the causes of observed climatic change

![]()

French diplomat and historian Abbé Jean-Baptiste Du Bos (left). David Hume (right) and the cover page of one of his collections of essays (centre).

David

Hume (1711–1776) was a a key figure in the history of Western philosophy

and the Scottish Enlightenment.

Hume

also recognized that climate was not stable, but was undergoing changes, and for

the time being towards better (milder) conditions. He assumed that this climatic

change was caused by human activities.

To

illustrate the character of the unfavourable past climatic conditions in Europe,

Hume in 1750 published an essay entitled “Of the Populousness of Ancient

Nations”. In this essay he argued that the climate of Europe and the

Mediterranean region had been colder in ancient times and that the Tiber River,

which never freezes now, often froze in past times. Citing the French diplomat

and historian Abbé

Jean-Baptiste Du Bos (1670-1742), he writes “The annals of Rome tell us

that in the year 480 AD the winter was so severe that it destroyed the trees.

The Tiber River froze in Rome, and the ground was covered with snow for forty

days. At present the Tiber no more freezes at Rome than the Nile at Cairo.”

Hume also contrasted the current mild climate of France and Spain with accounts

drawn from different ancient writers (Fleming 1998).

Concluding

that climate was changing to the better, Hume suggested that the observed

improvement (moderation) of the climate had been caused by the gradual advance

of cultivation in the nations of Europe. He also believed that similar, but much

more rapid changes were occurring in North America as the forests were cleared

by the European settlers (Fleming 1998).

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1700-1750:

Rostocker Harbour closed by sand on Falster, Denmark

Denmark

seen from SSW, with southern Sweden in the distance (upper left), and northern

Germany to the right. The location of Rostocker Harbour in southernmost Falster

is indicated by the arrow. The peninsula Jutland in the foreground measures

about 400 km from south to north. Along the southern west coast of Jutland a

series of barrier islands are seen. Picture source: Google Earth.

In

contrast to what might be expected, the former Rostocker Harbour is not located in

northern Germany at the city Rostock, but near the southernmost point of

Denmark, on the island Falster. Until about 1750 AD this was the main Danish port

for transporting goods between eastern Denmark and Germany by ship. Today the

‘harbour’ is dry and located 1.5 km inland.

The southern part of the island Falster is elongated and narrow, formed around a terminal moraine deposited by an ice stream flowing from the southern Baltic during the final part of the Weichselian glaciation, presumably around 15,000 years ago. The moraine ridge has a light curvature towards west (see picture below).

Southern

Falster seen from S. The uppermost panel shows the modern landscape with the

present ferry town Gedser. The southern part of Falster measures about 3 km

across (east-west). The lower panel shows the geographical situation during the

Little Ice Age, with Rostocker Harbour open and in operation. The red area

indicates the approximate extension of the terminal moraine formed by a

Weichselian glacier flowing from the Baltic to the east (right), the yellow

areas show a chain of barrier island in front of the eastern coast, and the blue

area is below sea level and covered by the sea.

Original picture source: Google Earth.

For

several thousand years following the termination of the Weichselian glaciation

the present sea area around Falster was dry land, with the exception of a big

river draining a large lake (the Ancylus

Lake) filling the extensive Baltic depression. However, the gradual melting of the

remaining ice sheets in North America, Greenland and Antarctic brought

about a transgression of the former land area between Denmark and Germany about

6-7000 years ago. In southern Falster only the elongated moraine ridge escaped

submersion, and formed a curved peninsula. During the Little Ice Age (ca.

1300-1900 AD) an increased frequency of strong storms resulted in both coastal

erosion in the area as well as the accumulation of so-called barrier islands

beyond the coastline, controlled by the local depth, sediment and wind

conditions.

Barrier Islands is a coastal landform consisting of relatively narrow islands of sand parallel to the mainland coast. They usually occur in chains, consisting of anything from a few islands to more than a dozen. Excepting the tidal inlets that separate the individual islands, a barrier island chain may extend uninterrupted for over a hundred kilometres, such as is seen along the modern Danish and German North Sea coast (uppermost figure).

Barrier islands usually

form perpendicular to the dominant wave direction. In the case of southern

Falster this is towards east, as there is several hundred kilometres of open sea in

this direction, and for that reason the barrier islands accumulated up to about

2 km east of the main coast, leaving a sheltered sea area (locally known as Břtř

Nor) between

the peninsula and the barrier islands, representing a fine, natural harbour.

There is only little tidal variation in the Baltic, but wind and air pressure variations nevertheless causes frequent sea level variations, leading to rapid water movement in and out of the inlets between individual barrier islands. One of the main Little Ice Age inlets in the chain of barrier islands along southern Falster was found near the southern end of the chain, wherefore a harbour was established at the village Gedesby shortly inside the inlet. With time this harbour developed into the most important harbour for exchange of goods between eastern Denmark and Germany. As the main nearby harbour in northern Germany was located near the city Rostock, the harbour at Gedesby was known in Denmark as Rostocker Harbour.

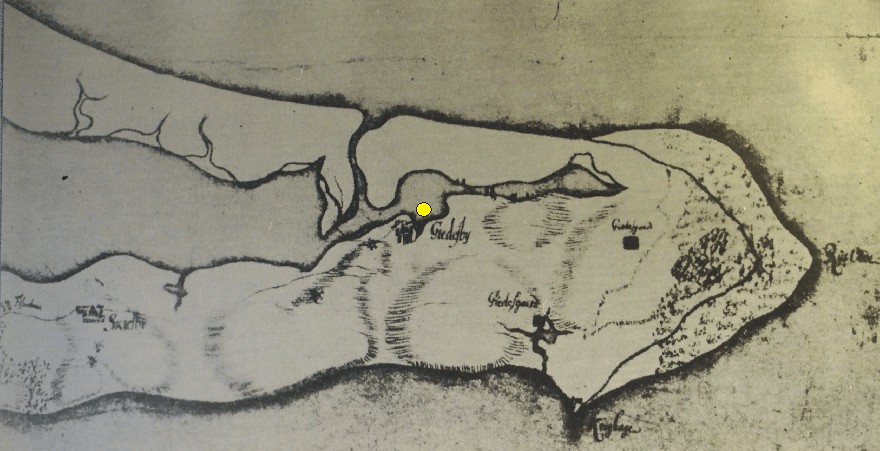

Map

from 1700 by Hans Heinrich Sheel, showing the southern part of the island

Falster. Please note that north is shown towards left. The town Gedesby is indicated

near the centre of the map, as

is the chain of barrier islands beyond the

mainland coast. The position of Rostocker Harbour is shown by the yellow dot.

By

this, since 1135 AD, Gedesby was one of the most important towns on Falster,

with about 40 farms. In the year 1551 Gedesby obtained a monopoly on the ferry

connection to Germany, with the obligation of providing four ferries, each with

space for 12 riders with horses and equipment, at any time. In 1571 AD Queen

Sofie to the Danish King Frederik II ordered the building of a ferry hotel (a

‘ferry kro’) at the harbour, to ensure proper lodgement in Gedesby for

herself and her family, whenever she wanted to visit her former homeland

(Germany).

In

the early 18th century the Danish

King Frederik IV (1671-1730) became allied the Russian tsar Peter

the Great (1672-1725), who promised Russian fleet support to a planned

Danish invasion of southern Sweden (Skĺne). While the Russian battle fleet was

waiting further north, tsar Peter the Great wanted to visit the royal castle in

the town Nykřbing Falster (see uppermost panel) in July 1716. He arrived with

his flag ship at Rostocker Harbor, and apparently stayed overnight in the ferry

hotel in Gedesby, before traveling on land to Nykřbing Falster (Křrvel

2010).

However,

several strong storms during the coldest period of the Little Ice Age (1650-1720

AD) and the resulting enhanced near-shore transport of sand along the barrier

islands gradually lead to increasing difficult sailing conditions, and the inlet

to Rostocker Harbour slowly became filled with sand. On a map from 1766 the

sailing route to the inlet is still indicated, but the harbour had to be given

up shortly after, as the inlet gradually became too shallow because of

accumulating sand.

Today

the entire Břtř Nor has been drained by pumping following the construction of

a dike along the eastern coast of the barrier islands (Brandt

1997), and the former Rostocker Harbour is now located about 1.5 km inland

from the modern east coast of Falster. However, the former harbour is still

clearly visible in the landscape as a topographic depression 150-200 m east of Gedesby

Church (picture below).

Rostocker

Harbour on July 13, 2013, looking SE. The forest in the far distance is standing

on one of the former barrier islands, and the terrain in the foreground is below

sea level.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1772:

Vernagtferner in Austria advances again into Rofental and ice dammed Rofener

Eissee reforms ![]()

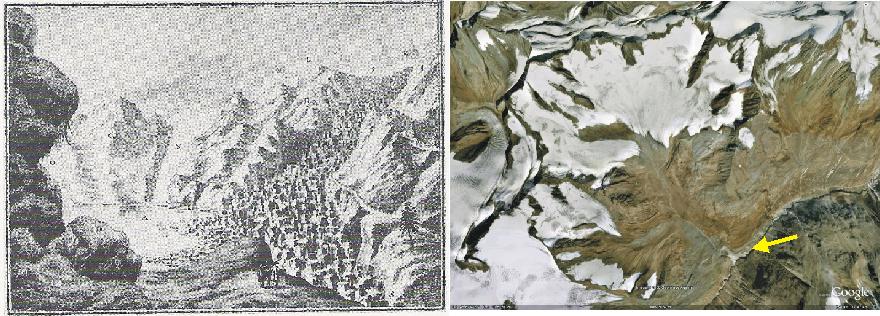

The Rofen ice lake on August 16, 1772, as shown on copper plate III in Walcher 1773 (left). In the background it can be seen that the ice dammed lake has filled the valley Rofental and reaches all the way to the termini of the glaciers Hintereisferner and Hochjochferner. The glacier Vernagtferner itself is shown heavily crevassed. The modern (2007) glacier Vernagtferner is seen on the satellite photo (right; picture source: Google Earth).The yellow arrow indicate the point of view in the illustration to the left.

The period 1770-1774 is known to be a period with renewed advance of the glacier Vernagtferner in Tirol, Austria (Hoinkes 1969). A booklet entitled "Nachrichten von den eisbergen in Tyrol" was published in 1773 by Joseph Walcher, Professor of Mechanics at the University of Vienna, after a visit to the glacier in 1772. This booklet contains several interesting suggestions for protective measures (Hoinkes 1969). Among other copperplates it includes the engraving reproduced above, showing the badly crevassed lower tongue of the Vernagtferner and the Rofen ice lake extending upvalley to the glaciers Hintereisferner and Hochjochferner on August 16, 1772.

Click here and here to read about previous Little Ice Age advances of the Vernagtferner. A later advance is described here. Click here, here and here to read about the glacier retreat following the Little Ice Age advances.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1783-1784:

The Laki eruption in Iceland ![]()

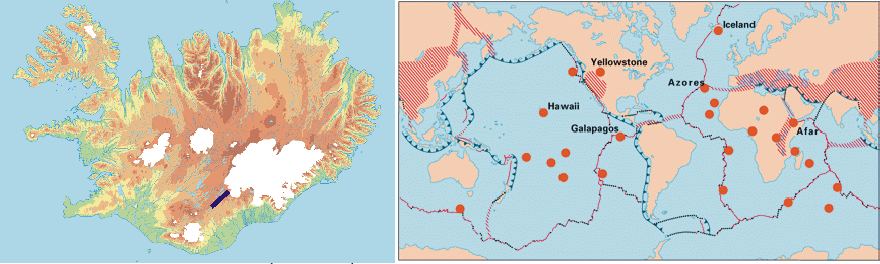

Topographic map showing Iceland with the Laki fissure indicated by a black line (left). Geological plate boundaries and hotspots (red dots) on planet Earth (right).

Laki

or Lakagígar (Craters of Laki) is a volcanic fissure in southern Iceland, which

has been active several times in historical time. In 1783 Laki erupted together

with the adjoining Grímsvötn volcano in the large ice cap Vatnajökull,

killing more than 50% of the livestock, and leading to a famine which killed

about 21% of the total population in Iceland.

The

eruption started on June 8, 1783, with about 130 craters along the fissure

erupting explosively, because the rising lava met huge amounts of ground water

on its way towards the terrain surface. Along the fissure line lava fountains

were estimated to have reached heights of 800-1400 m. The eruption rapidly

became known in Iceland as the Skaftáreldur (the Skaftá river fires).

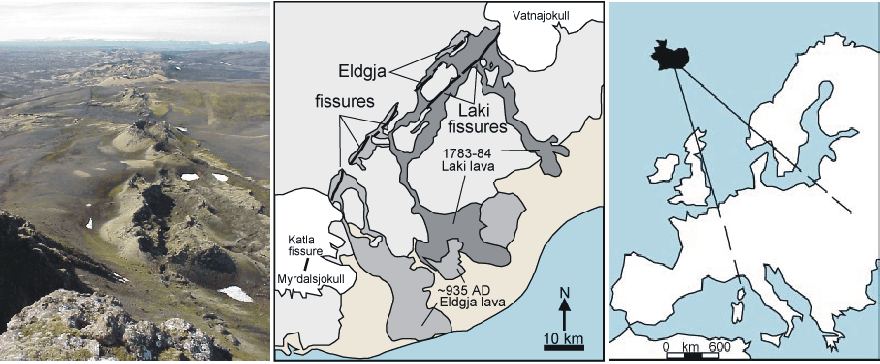

Volcanic craters along the Laki fissure in southern Iceland (left). Map showing extent of lava streams derived from the Laki eruption in 1783-1784 and the previous Eldgja eruption in year 935 (centre). Map showing regions in Europe affected by ash fall from the Laki eruption (right).

Henderson

(1818) publiced a vivid acount of the initial phases of the Laki eruption:

“From the 1st to the 8th of June, 1783, the inhabitants of West Skaftafell's

Syssel were alarmed by repeated shocks of an earthquake, which, as they daily

increased in violence, left no reason to doubt that some dreadful volcanic

explosion was about to take place. Pitching tents in the open fields, they

deserted their houses, and awaited, in awful suspense, the issue of these

terrifying prognostics. On the morning of the 8th, a prodigious amount of dense

smoke darkened the atmosphere, and was observed to be continually augmented by

fresh columns arising from behind the low hills, along the southern base of

which the farms constituting the parish of Sida, are situated….

….

A strong south wind prevented the cloud from advancing over the farms; but the

heath, or common, lying between them and the volcano, was completely covered

with ashes, pumice, and brimstone. The eruption had now actually commenced; and

the raging fire, as if sublimated into greater fury by the vent it had obtained,

occasioned more dreadful tremefactions, accompanied by loud subterraneous

reports, while the sulphureous substances that filled the air, breaking forth

into flames, produced, as it were, one continued flash of lightning, with the

most tremendous peals of thunder that were ever heard. The extreme degree to

which the earth in the vicinity of the volcano was heated, melted an immense

quantity of ice, and caused a great overflow in all the rivers originating in

that quarter….

….

Upon the 10th, the flames first became visible. Vast fire-spouts were seen

rushing up amid the volumes of smoke, and the torrent of lava that was thrown up,

flowing in a south-west direction, through the valley called Ulfarsdal, till it

reached the river Skaptá, when a violent contention between the two opposite

elements ensued, attended with the escape of an amazing quantity of steam but

the fiery current ultimately prevailed, and, forcing itself across the channel

of the river, completely dried it up in less than twenty-four hours; so that, on

the 11th, the Skaptá could be crossed in the low country on foot, at those

places where it was only possible before to pass it in boats. The cause of its

desiccation soon became apparent: for the lava, having collected in the channel,

which lies between high rocks, and is in many places from 400 to 600 feet in

depth, and near 200 in breadth, not only filled it up to the brink, but

overflowed the adjacent fields to a considerable extent; and, pursuing the

course of the river with great velocity, the dreadful torrent of red-hot melted

matter approached the farms on both sides, greatly damaged those of Hvammur and

Svinadal to the west, and that of Skaftárdal to the east…..”

Moss covered lava fields near Kirkjubćjarklaustur in southern Iceland, derived from the Laki 1783-1784 eruption. In the background the southern part of the ice cap Vatnajökull is seen. The highest summit is Örćfajökull (2109 m asl.), the highest active volcano in Iceland. It has erupted twice in historical time, in 1362 and 1727. Photo taken September 16, 2003.

The

Laki eruption produced about 15 km3 lava, which covered huge areas in southern

Iceland. Most of the lava erupted during the first five months of the eruption.

In addition, clouds volcanic ash and poisonous fluorine/sulphur-dioxide compounds

were released around the eruption site, killing more than 50% of the Icelandic

livestock.

The

eruption ended on February 7, 1784. The Grímsvötn volcano, from which the Laki

fissure extends, was also erupting at the time from 1783 until 1785.

The

eruption of Laki was probably one of the most devastating events to occur in

modern Icelandic history. Already greatly weakened by the harsh climate of the

Little Ice Age, coupled with the rigours of exploitation under an uncaring and

exploitative Danish trading monopoly, Iceland was little prepared to withstand

the consequences of this natural disaster.

Mainly

because of massive losses to livestock during and after the eruption, and later

by starvation caused by the destruction of grasslands and home-fields by

volcanic ash, the death-rate soared in the years immediately following the

eruption. Prior to the eruption the Icelandic population numbered about 50,000,

and declined more than 10,000 following the eruption. According to a

contemporary source (Nicol 1844), about 19,488

horses, 6801 horned cattle, and 129,937 sheep was lost in Iceland 1873-1885

because of the eruption.

It

took about 40 years before the population was back to the pre-eruption level,

and farms destroyed or abandoned were either reconstructed or re-inhabited. Many

people decided to leave

Central England temperature series 1750-1830. The length of the Laki-Grímsvötn 1783-1785 volcanic eruption is indicated by the dark blue bar. The immediate cooling effect of the eruption is clearly seen, both summer and winter. The bar 1785-1793 indicate a subsequent period with relatively low air temperatures recorded in Central England, especially during the growing season (summer). This period may at least partly be due to a higher atmospheric content of aerosols in the years following the eruption. These graphs has been prepared using the composite monthly meteorological series since 1659, originally painstakingly homogenized and published by the late professor Gordon Manley (1974). The data series is now updated by the Hadley Centre and may be downloaded from there by clicking here. A graph showing the entire Central England temperature series since 1659 can be seen by clicking here.

The

total volume of volcanic ash (tephra) produced by the Laki eruption has been

estimated to more than 0.9 km3. The summer of 1783 was warm and a rare high

pressure zone located over

The gases and ash derived from the Laki eruption were carried by the convective eruption column to altitudes of about 15 km in the atmosphere, and the aerosols caused a significant cooling effect in the Northern Hemisphere, as is documented by the Central England meteorological record. The sulphur hazes may well have been the primary cause of the cooling that occurred after the large Laki 1783-1785 eruption.

In

In North America, the winter of 1784 was the longest and one of the coldest on record. It was the longest period of below-zero temperature in New England, the largest accumulation of snow in New Jersey, and the longest freezing over of Chesapeake Bay. There was ice skating in Charleston Harbour, a huge snowstorm hit the south, the Mississippi River froze at New Orleans, and there was ice in the Gulf of Mexico.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1786:

The snow storms of December 1786 in New England ![]()

The global cooling following the Laki eruption in Iceland 1783-1784 was felt worldwide. The winter of 1786-1787 set in very early in Maine, USA (Perley 2001). At Warren the St. George's River was frozen thick on November 15, and horses and sleighs was able to use the ice cover for transport, all the way to the mouth of the river. It did not break up until the latter half of March 1787.

By November 20, the harbour of Salem, Massachusetts, was frozen over beyond Naugus Head, and the Connecticut River was frozen so rapidly that, within 24 hours after boats passed over it the ice had become thick enough to bear people, horses and sleighs. Between 30 and 40 ships were frozen in, before being able to leave.

December 1786 was unusually severe with frequent snow storms. A very strong storm began December 4, resulting in flooding and the loss of several ships. Wind pressure and low air pressure lifted the ocean surface near Boston, and water overflowed the 'pier'. Quantities of wood and lumber floated away. Great quantities of snow covered the landscape so deep, that travel became difficult. At Rockland, Maine, snow remained on the ground as late as April 10, 1787. Later the same week, another terrible snow storm with strong northeast wind began, continuing for about two days. This storm deposited huge amounts of snow, so travel now became extremely difficult, and in many places impossible (Perley 2001). In Boston, a number of people had to be employed in 'levelling' the snow in the streets. The next day the Massachusetts Gazette of the time said, "It is hoped they and many others will turn out this day for the same laudable and necessary purpose." The roads were completely filled from wall throughout New England. This was one of the most difficult storms to withstand that was ever experienced in New England. Several persons who were out in it became lost and died in the snow.

The storm had serious consequences along the coast. In Long Island Sound, many vessels went ashore, and some were entirely lost.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1786:

Observations on glacier size in Lituya Bay, south-eastern Alaska

![]()

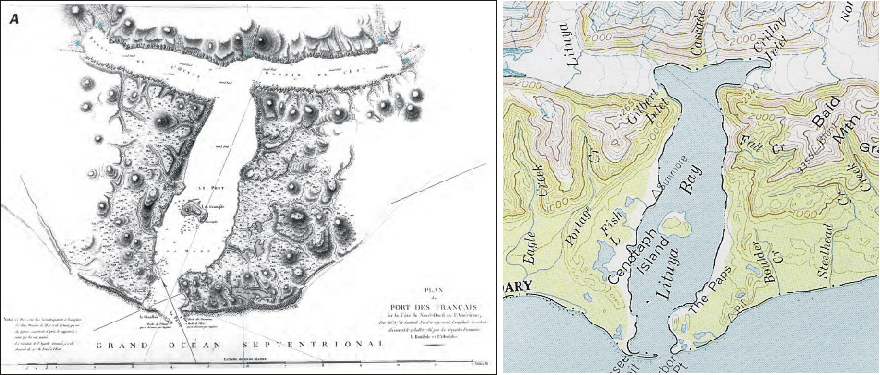

La Pérouse's 1786 map of Lituya Bay, showing pairs of glaciers reaching the two heads of the T-shaped fjord (left), reproduced from Glaciers of Alaska (Molnia 2008) . The length of the outer part of the fjord system is about 8 km. Map showing the geography around Lituya Bay in 2004 (right; DeLorme 2004). The net glacier change from 1786 to 2004 is that each of the two pairs of glaciers have coalesced and advanced more than 3 km. On both maps, north is diagonally towards the upper left corner.

In July 1786, Jean François de Galaup de La Pérouse led two ships, the Boussole and the Astrolabe, in an expedition to the coast of the St. Elias Mountains, southeastern Alaska (58o40' N). A map published in 1797 after the expedition is reproduced in the latest (October 4, 2008) U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) release of Professional Paper 1386K, Glaciers of Alaska by Bruce F. Molnia. This publication represents the eighth chapter of the monumentary Satellite Image Atlas of Glaciers of the World, edited by Richard S. Williams, Jr., and Jane G. Ferrigno.

La Pérouse's map of Lituya Bay with glaciers is reproduced on page 22 as figure 9A (see map above). The text in Glaciers of Alaska shortly describing the La Pérouse expedition is reproduced below:

In Lituya Bay, a T-shaped fiord with numerous glaciers at its head, he set up a scientific observatory on Cenotaph Island. He clearly had knowledge of glaciers because his log describes their locations and characteristics. His map of Lituya Bay (above) accurately depicts water depths within the bay and the location of five glaciers at the upper ends of the bay. La Pérouse’s narrative describes how several members of the expedition attempted to climb one of the glaciers at the head of the western arm of the bay. He stated that “With unspeakable fatigue they advanced 2 leagues, being obliged at extreme risk of life to leap over clefts of great depth; but they could only perceive one continued mass of ice and snow, of which the summit of Mount Fairweather must have been the termination”. Drawings by expedition members Lieutenant de frégate Blondela and Gaspard Duche de Vancy show Cascade Glacier at the head of Lituya Bay.

Many glaciers in Alaska are experiencing negative mass balance and volume reduction in the early 21st century. But notwithstanding this, the glaciers at Lituya Bay are still in the early 21st century at a more advanced position than in 1786.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1788:

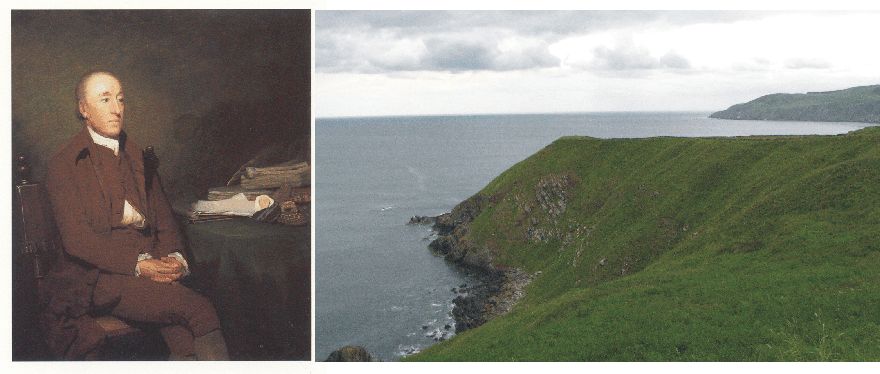

James Hutton visits Siccar Point ![]()

James Hutton (left). Siccar Point on the Berwickshire coast, looking east on 17 June 2008 (right).

James

Hutton (1726-1797) was born in Edinburgh on 3 June 1726. During his education he

studied law, chemistry and eventually became a Doctor of Medicine in 1749. He

inherited two farms near Reston in Berwickshire east of Edinburgh, and set about making

improvements, introducing farming practices from other parts of Britain.

By

this, he became highly interested in both meteorology and geology, and became

very found of studying what was exposed by digging drainage channels on his

properties. By this he noted that some types of solid bedrock apparently

contained remnants of dead animals of unknown age. Around 1760 his geological

interest had grown considerably, and he was beginning to form his own opinion on

many geological issues. He was soon realizing that the Biblical age of Earth

(6000 years old) was much to short a time range to explain his observations on

past environmental changes. From 1785 he began to publish his ideas for a wider

audience, but was generally met with refutations, as he had no really convincing

geological evidence to support his ideas with. So the general opinion of planet

Earth being about 6000 years old prevailed.

In

1788 James Hutton visited the Berwickshire coast with two friends, John Playfair

and Sir James Hall (McKirdy et al. 2007).

Between Dunbar and Eyemouth they visited a small peninsula called Siccar Point (see

photo above). Here they found a peculiar geological outcrop, showing two

geological units of sandstone and greywacke, but with the individual layers

standing almost perpendicular to each other (see photo below). This was the very first example of what

later was to be known as a geological

unconformity.

Hutton's unconformity at Siccar Point on 17 June 2008, looking NE. Both geological units consist of parallel sediment layers (Red Sandstone and Greywacke) deposited almost horizontally in a water body. The significant change in orientation across the unconformity signals that a major reorganisation of what was up and down must have taken place during the time between the deposition of these two units.

Hutton and his friends immediately grasped the high significance of what they saw at Siccar Point. Hutton reasoned that both types of rock must have been deposited on the bottom of an ocean, and that the almost 90o tilting visible (see photo above) required substantial changes in the surface form of the planet. In between the deposition of the two units there must have been a period of unknown length, where layers must have been eroded and tilted, leading to formation of the unconformity. This was clearly proof of a very dynamic planet. This conclusion was in contradiction to the notion of a essentially stable environment in equilibrium since the days of creation, a paradigm which in Europe had made scientific progress difficult. A further realisation of equal importance was that the geometrical relationship between the two sets of layers could not have formed in the seven days prescribed in the Bible for the formation of the Earth. Indeed, any timescale measured in terms of human existence would be insufficient to accommodate the chain of events that Hutton and his companions had deduced by analysing the geological section at Siccar Point.

When

Hutton put forward his revolutionary concept of deep time and an ever

changing dynamic planet, this was not accepted overnight by the scientific

community. It was first after his death in 1797 that the concept of extensive

time for the formation of the present surface of the planet slowly gained

acceptance, together with the understanding that the environment and landscapes always are changing,

sometimes slowly, sometimes rapid. Hutton’s legacy

thereby was to free later generations of scientists from a mental straightjacket, allowing

them to think freely and thereby make science develop

and blossom. The famous geologist Charles

Lyell enthusiastically embraced Hutton’s ideas and clearly presented them

in his now classic book, Principles

of Geology. Charles

Darwin read Lyell’s book while sailing on the Beagle expedition. Hutton's

idea of an “abyss of time” provided

It was first much later when Alfred Wegener in 1912 proposed his theory of continental drift (Kontinentalverschiebung) that the importance of the always ongoing geological processes for global climate began to dawn for geologists. It also took some time before the significance of climate changes on sedimentary strata like those seen at Siccar Point began to be understood. Actually each layer seen in the rocks at Siccar Point (photo above) reflects some kind of environmental change, either on land or in the ocean, or within both. But Hutton's observations at Siccar Point was the very starting point for realising that planet Earth is a highly active planet, where different processes never are in perfect equilibrium. Environmental change is always occurring.

Hutton’s observations and deductions at Siccar Point thus had profound effect for the subsequent scientific development, especially within earth and biological science. Siccar point is arguably the most important geological site in the world (McKirdy et al. 2007).

Lateral drainage channel at Siccar Point, looking SW on 17 June 2008. The marked valley is dry today, but was presumably cut by meltwater flowing along the southern margin of a Weichselian glacier draining east along the Firth of Forth, eastern Scotland.

The profound dynamic nature of planet Earth

demonstrated by Hutton's unconformity at Siccar Point is emphasised by the

geomorphology in the near sourroundings. In contrast to Hutton and his friends,

who came to Siccar Point by boat, most visitors today will come by car, to walk

the final kilometre to the coastal site. The Siccar Point parking place is

located in a peculiar dry valley (see photo above). This is a relict meltwater

channel, cut by meltwater running along the southern margin of a big glacier

flowing east along the Firth of Forth topographic depression about 22,000 years

ago. This might well have been the same ice stream which was responsible for

another famous geological locality at Blackford

Hill in southern Edinburgh,

where peculiar scratches on bedrock were identified as as

being the result of glacier action by Jean

Louis Agassiz in 1840, thereby giving the glacial hypothesis a significant

momentum 52 years after Hutton's visit at Siccar Point. Our scientific

understanding of the dynamic nature of planet Earth made huge progress during

this short time span from 1788 to 1840, both with regard to geology and climate.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1789:

Storofsen – the largest historical flood in ![]()

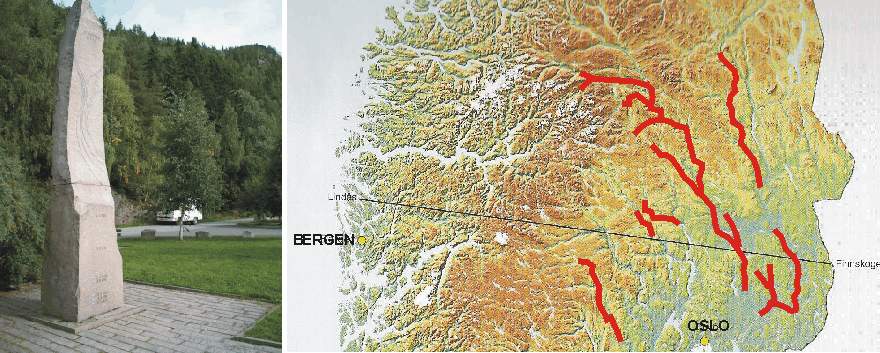

Memorial for the 1789 Storofsen flood in Gudbrandsdalen, eastern South Norway (left). Map showing southern Norway, with the worst affected valleys indicated (right).

Presumably

still under influence of the 1784-1785 Laki volcanic eruption in

Heavy

and persistent rain began in southern

The

still frozen ground inhibited rapid percolation of water at many places, and on

sloping ground instable conditions arose on top

of the still frozen ground in thawed and now waterlogged sediments. At other places, solid bedrock

below loose sediments may have acted in the same

manner. The result was a large number of mudflows and landslides in eastern

A

large number of houses and farms were destroyed by the flooding and by mud and

stones from landslides and mudflows. It has been estimated by Dřrum

(2008) that more than 950 farms were demolished. In addition valuable

farming fields were covered by thick layers of fluvial sand and gravel.

Storofsen was indeed a national disaster for

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1789-1793:

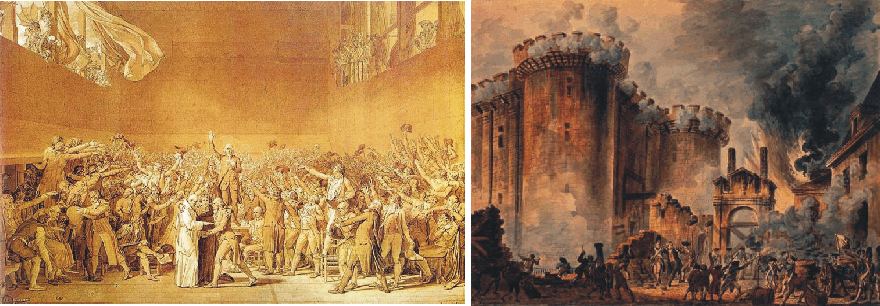

The French Revolution; Part 1 ![]()

The political and

socioeconomic nature of the French Revolution in 1789 is disputed among

historicans. But most historical analyses identify a number of economic factors

as being important among the causes of the Revolution.

The French King Louis

XV had fought many wars, thereby significantly weakening the French national

economy. The country had been virtually bankrupted by first the Seven Years' Was

and then the American War. The national debt had grown to huge porportions. The social burdens

caused by war included the huge war debt, made worse by the monarchy's military

failures and ineptitude, and the lack of social services for war veterans. High

unemployment and high bread prices, causing more money to be spent on food and

less in other areas of the economy was another important factor for widespread

social unrest. In addition, there was widespread resentment of royal absolutism,

there was resentment by the ambitious professional and mercantile classes

towards noble privileges and dominance in public life, and there was resentment

of clerical privilege and aspirations for freedom of religion. And then, of

cause, there was the almost total failure of Louis XVI and his advisors to deal

effectively with any of these problems.

Widespread famine and malnutrition among the most dissatisfied groups of the French population in the months immediately before the Revolution were presumably the single igniting factor. Since the Laki volcanic eruption in Iceland 1784-1785 summers had been cool in Europe and harvest poor. It was in France, that several of the following weather extremes seem to have been most serious. 1785 produced the coldest March recorded in much of Europe, and extended what was already an outstandingly severe winter. This was followed by a year of drought, with only 67 per cent of the expected annual precipitation falling in Paris (Lamb 1995). This resulted in a forage crisis on the French farms, and many cattle had to be slaughtered. The French peasants at that time ate bread made of rye or oats, and only the upper classes was able to afford wheaten bread. Even so the dearth produced by the failing harvest meant that about 55 per cent of the poorer classes' earnings went on bread alone. To make things even worse, in 1789 the price for bread was increased from 8 to 14 sous. This caused widespread dissatisfaction, to put it mildly.

In 1786 the French government ran out of ready access to lenders, and the minister of finance was forced to inform Louis XVI that the situation could only be corrected by imposing taxes. In 1787 Louis XVI’s therefore attempted to solve worsening financial situation by introducing a new land tax that would, for the first time, include a tax on the property of nobles and clergy, instead of the poor classes. These rich groups were not entirely happy with this initiative. In fact, the attempt to raise taxes provoked a furious outcry from the men of property, in particular, the nobility. The direct cause of the French Revolution was thus not the state's attack on the poor, but on the rich.

After

bitter exchanges, the King was forced to Summon the Estates-General, a kind of

national assembly of the three estates, which had last been convened at the

beginning of the 17th century, to get his way (Harvey

2006). In the time leading up to the planned convention in 1788

there was was growing concern that the King and the government would

attempt to fix an assembly to its liking. To avoid this, the Parliament of Paris

proclaimed that the Estates-General would have to meet according to the forms

observed at its last meeting, without any changes. In addition, there was

discussions about how to vote. Fuelled by such disputes, resentment between the

elitists and the liberals began to grow.

Things were now

beginning taking their own course, driven by peoples feeling of injustice. The

assembly, now meeting as the Communes (English: "Commons"). On the 17

June they declared themselves the National Assembly, an assembly not of the

Estates but of "the People." They invited the other orders to join

them, but made it clear they intended to conduct the nation's affairs with or

without them.

In an attempt to put a

brake on this threatening development Louis XVI tried to prevent the

Assembly from convening by ordered the closure of the Salle des États where the

Assembly met. The official excuse was that the carpenters needed to prepare the

hall for a royal speech in two days. The cool and wet summer did not encourage

the Assembly to conduct an outdoor meeting, so it was decided to moved the

deliberations to a nearby indoor tennis court. This is where the famous Tennis

Court Oath was given on June 20, 1789. It was decided not to end the meeting

before they had given France a constitution. Most of the representatives of the

clergy soon joined the meeting, as did 47 members of the nobility. Messages of

support for the Assembly poured in from Paris and other French cities. On 9 July

the Assembly reconstituted itself as the National Constituent assembly.

By this time, Jaques

Necker was in his second turn as finance minister. To calm public feelings, he

suggested that that the royal family should live according to a more modest

budget than hitherto. Louis XVI was, however, not inclined to follow this

suggestion and fired Necker. The following day (July 12) he completely

reorganised the finance ministry.

Many Parisians presumed

Louis's actions to be the start of a royal coup by the conservatives and began

open rebellion when they heard the news the next day. They were also afraid that

arriving Royal soldiers had been summoned to shut down the National Constituent

Assembly, which was meeting at Versailles. The Assembly went into non-stop session to prevent eviction from their meeting place. Paris was soon consumed

with riots, anarchy, and widespread looting.

On July 14, 1789, the

insurgents set their eyes on the weapons and ammunition depots inside the

Bastille fortress, which also was a symbol of tyranny by the monarchy. After

several hours of combat, the prison fell in the afternoon. Rumours were that a

high number of political prisoners was held here, but only seven prisoners was

found, among them two noblemen kept for immoral behaviour, and one murder suspect.

Confronted with this

rapid development, the King and his military supporters sensibly backed down and

attempted to reconciliate with the people. The president of the Assembly at the

time of the Tennis Court Oathbecame the city's mayor under a new governmental

structure known as the commune. On October 6, 1789, the King and the royal

family moved from Versailles to Paris under the protection of the National

Guards, thus legitimising the National Assembly.

Many French nobles,

however, were not impressed by this apparent reconciliation of King and people.

They began to flee the country, some of whom began plotting civil war within the

kingdom and agitating for a European coalition against France.

The Revolution also

brought about a massive shifting of powers from the Roman Catholic Church to the

state, and the remaining clergy was turned into employees of the State and

required that they take an oath of loyalty to the constitution. The pope never

accepted the new arrangement, and it led to a schism between those clergy who

swore the required oath and accepted the new arrangement and those who refused

to do so.

In late 1790, several small counter-revolutionary uprisings broke out and futile efforts took place to turn all or part of the army against the Revolution. The French army, however, faced considerable internal turmoil. The new military code, under which promotion depended on seniority and proven competence (rather than on nobility) alienated some of the existing officer corps, who left the country or became counter-revolutionaries from within.

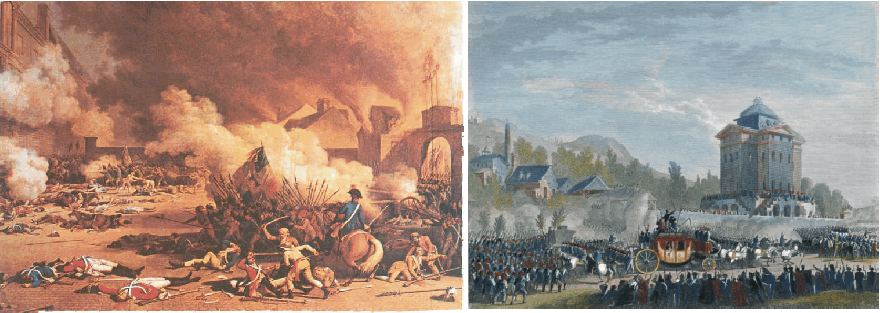

The

Paris Commune

and the storming of the Tuileries Palace

on August 10, 1792 (left). The return of

the royal family to Paris on June 25, 1791, colored copperplate after a drawing

of Jean-Louis Prieur

(right).

Louis XVI was basically

opposed to the course of the Revolution, and on the night of 20 June 1791 the

royal family fled from Paris disguised as servants, while their servants were

dressed as nobles. However, the next day the King was recognised and arrested and

with his family paraded back to Paris under guard, still dressed as

servants. Back in Paris, the Assembly provisionally suspended the King, which

together with Queen Marie Antoinette remained held under guard.

On the night of 10

August 1792, insurgents, supported by a new revolutionary Paris Commune,

assailed the Tuileries, where the royal family was held. The King and queen

ended up prisoners and a short meeting in the Legislative Assembly suspended the

monarchy. On September 20, 1792, the monarchy was officially abolished and

France declared a republic.

Louis XVI were accused of being conspiring with the enemies of France, and on January 17, 1793 he was condemned to death for "conspiracy against the public liberty and the general safety" by a close majority in the now ruling Convention. The execution was carried out 21 January, which lead to declarations of war from several European countries. Quen Marie Antoinette was executed on 16 October 1793.

Click here to jump back to the list of contents.

1793:

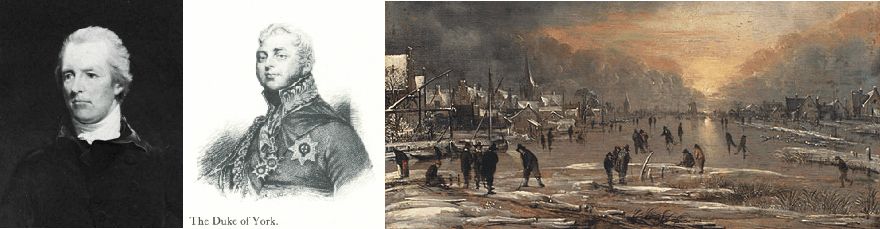

France declares war on Britain ![]()

Prime minister William Pit as young, around 1790 (left). The Duke of York (centre). People skating on frozen channel in Holland in the late 18th century (right).

In Britain things were

difficult around the beginning of 1793. The situation was exacerbated by a

sudden economic downturn in 1792 after several years of economic expansion,

which had resulted in increasing bread prices. Indeed, from

around 1789 to 1802 the harvest in Britain was poor, and especially in 1792

(Harvey 2006). In November 1792 the number of

bankruptcies was double the worst total ever recorded before. All of this

clearly contributed to a general paranoia on the issue of public security at a

time characterised by immense social and economical change. Understandably the

young prime minister William Pitt reflected the temper of the times.

At the age of only 24, William Pitt (1759-1806) became

News of the execution of Louis XVI in Paris arrived in London on 23 January 1793. Perhaps under the influence of

the general paranoia, the Revolution's last ambassador to Britain, the Marquis

de Chauvelin, was promptly ordered to leave the country. When he reached Paris

29 January there was an outcry. Also in France, people understandably were

generally stressed and not feeling especially secure.

An embargo was imposed on Dutch and British shipping and General Dumouriez was ordered to invade Holland. On 1 February the Convention declared war on both Holland and Britain and also urged the British people to rise up against their masters. The news of this arrived in London on 7 February, and on 11 February 1793 the British King George III, following the advice of Prime Minister Pitt declared war on France.

A British military intervention in north-west Europe was planned. Prime Minister Pitt had good reason to believe that the war would be short, as France obviously was in a very weakened state. In fact if would not end before the final defeat of Napoleon in 1915 at Waterloo. Britain's formal allies, the Prussians, were deeply suspicious of this new rapprochement with Austria. On their side, however, the Austrians were delighted by the British enmity towards France, and the new chancellor, Baron Thugut, was extremely pleased to have a counterpoise to the Prussians, whom he detested almost as much as the revolutionary French.

The British decided to take the initiative. An expedition corps of 14,500 men was sent to Europe to seize Dunkirk, once a British possession. They were to be commanded by King George III's favourite son, the Duke of York, who had established himself with a drinking and gambling debt of 40,000 pounds within less than a year. Presumably King George III would like to put him out of the way of his creditors in London. Very unfortunately, the Duke also had the reputation of being military incompetent, but considering the weak opposition expected from France, this was not seen as a major problem. However, the British army was not, at this time, at its best. The battle for Dunkirk ended in complete disaster, and King George was furious at the humiliation of his favourite son, who himself took the defeat badly (Harvey 2006).

The Prussians immediately began to loose interest in the French war. Like everybody else they had anticipated an easy victory, and now it looked as if this was not to be had. So they decided to switch their attentions back to Poland. The Duke of York was then sent to reinforce the Austrians in their attempt of taking the town of Mauberge. But the Austrians was also defeated by the French army, and together with the British forced back towards the coast, where the armies took winter quarters. Next spring, the offensive would be renewed.

The British-Austrian spring 1794 offensive started well, and the two armies plunged on into France in April. In early May, however, they began to ran out of steam. On 8 May, the French counterattacked, and both British and Austrian went on the defensive, falling back along all their lines. Brussels fell to the French on 11 July 1794, and Antwerp later in the month. Holland's very survival was now at stake, and the Austrians were now in full flight towards The Rhine. Cologne fell in October.

Meanwhile the French invaded Holland, taking Eindhoven and Sluys in October. Only when they reached the river Wall, they were forced to pause, partly because the river was difficult to cross. The Little Ice Age winter 1794-1795 began early, and soon ice formed on all rivers, making them passable. The Dutch began to consider surrender to the French. Amsterdam was taken on 19 January 1795, and a few days later the French cavalry galloped across the frozen Zuiderzee to seize the large Dutch fleet, imprisoned as it was by sea ice. The British evacuated the remains of their army from the continent in April 1795.

The French imposed strict terms on the Dutch, including taking Maastricht, part of southern Holland, and the area around Flushing. From the British point of view, however, the worst effect was that the Dutch navy and part of the army were conscripted to the war against Britain. The Dutch fleet, although smaller than the French and the Spanish fleet, was highly respected for the courage of its seamen. This addendum to the French fleet for some years gave France a real possibility of invading the British Isles (Adkins and Adkins 2006). First during the Battle of Camperdown 11 October 1797 at the mouth of the Texel river most of the Dutch fleet was destroyed, and the threat of French invasion in Britain momentarily reduced.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

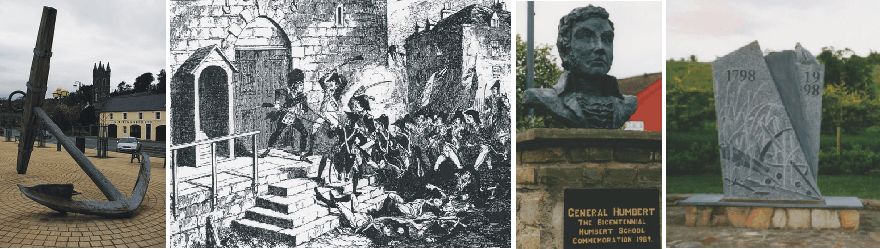

1796

and 1798: French invasion in![]()

Anchor from the French warship Surveillante (left). Irish rebellion in 1798 (centre left). Bust of General Humbert in Killala (centre right). Memorial for the Battle of Ballinarmuck (right).

The year 1796 was not a

very good year for the British war efforts against

Ireland

at that time therefore was in a state of continuous unrest. There was widespread resentment of

English rule, of gouging landlords, and of brutal discrimination against the

Catholic majority had been fanned and, in amateurish fashion, organized by the

United Irishmen movement. Theobald Wolfe

Tone, one of the founders of the United

Irishmen and a commissioned officer in the French Army, had lobbied ceaselessly

in

A formidable French

Armada of 16 ships of the line and 20 frigates and smaller ships with 18,000

soldiers sailed from

The British had

intelligence of the planned operation, and two squadrons had been assigned to

make intercept when at sea. Hoche’s expedition, however was initially favoured

with luck, and managed to avoid both flotillas.

Then things began to go

wrong. The French flagship carrying both admiral Morad de Galles and general

Hoche was lost. The rest of the invasion fleet meet successfully some twelve

miles of Bantry

Bay in south-western Ireland, but now the wind had increased and was to strong to navigate the narrow

strait leading to the bay and the planned invasion beach.

After several attempts of fighting the adverse wind, 12 ships actually made it into the bay, while 25

were blown away. Now the weather worsened further, and 10 ships were lost in the

hurricane-like storm. One of these ships was a frigate named Surveillante,

who was too storm damaged to make the return passage to

Five days later only

six battleships with four transports carrying 4,000 men still remained under

command under General Grouchy, general Hoche’s second-in-command. He decided

against landing and returned to

The following year 1798

there was again great unrest in Ireland, with several attempts

of rebellion. On

The French frigates Concorde, Franchise, and Médée,

carrying 1,070 French troops, 3 light field cannons, and 3,000 muskets, made

landfall at Kilcummin Head in north-western

In the beginning days

of the campaign general Humbert's forces were successful and actually defeated and

routed several British forces, send out to meet the French invasion. Many

untrained and unarmed Irish joined the invasion army. The "

On 8 September, however,

Humbert's small army was attacked by approximately 17,000 British troops north of

the

One month later, on 12

October 1798 a third invasion attempt was carried out. A larger French force

with about 3,000 men attempted to land in County Donegal near Lough Swilly,

accompanied by Wolfe

Tone himself. The Royal Navy however intercepted the French ships at sea,

and they had to surrender after a battle. Wolfe Tone was court-martialled and condemned

to death by condemned. He,

however, managed to commit suicide instead. Since then, there has been no invasion attempt on the

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.

1793-1799:

The French Revolution; Part 2 ![]()

Napoléon

Bonaparte in the coup

d'état of 18 Brumaire (detail

of an oil painting

by François Bouchot).

Facing local revolts

and foreign invasions in both the East and West of the country, the most urgent

government business rapidly became the war. The result was a policy through which

the state used violent repression to crush resistance to the government. Under

control of the effectively dictatorial Committee, the Convention quickly enacted

more legislation. Dissent from the political correct point of view was now

regarded as counterrevolutionary, and might be punished death by the guillotine.

The Reign of Terror however enabled the revolutionary government to avoid

military defeat, but most citizens of the now war-weary nation wanted stability,

peace, and an end to conditions that at times bordered on chaos. In the wake of

excesses of the Terror, the Convention therefore approved a new constitution on

August 22, 1795.

The new constitution created the Directory with a parliament consisting of 500 representatives and

250 senators. Executive power went to five "directors," named annually

by the Conseil des Anciens from a list submitted by the le Conseil des Cinq-Cents.

Many French citizens however distrusted the Directory, and the directors could achieve their purposes only by extraordinary means and by disregarded the constitution. To remain power, the directors routinely used draconian police measures to quell dissent. Moreover, the Directory found that war was an efficient technique for prolonging their power. The directors were thus driven to rely more and more on the armies, which also desired war and grew less and less civic-minded. In addition, the French state finances had been so thoroughly ruined during the earlier phases of the Revolution that the government could not have met its expenses without the plunder and the tribute of foreign countries.

The Directorate of

cause met serious opposition from different groups in France, including the

royalists. The army daily had to suppressed riots and counter-revolutionary

activities. In this way the army and its most successful general, Napoleon

Bonaparte, slowly gained more and more power. Back from Egypt, Bonaparte on

November 9, 1799, with his supporters engineered a coup, replacing the Directory

with a Consulate. This consisted of three consuls, but the main consul was

Napoleon, who eventually dispensed with the other two and ruled alone,

effectively establishing a military dictatorship. In 1804 this development was

followed by Napoleons proclamation

as Empereur (emperor), bringing a close to the French Revolution.

In

1789 the monarchs and aristocrats of Europe were chocked by the Revolution in

France, and in subsequent years the execution of the French royal family and the

bloodbath of Terror lost the revolutionaries what little support they had among

the ordinary people of other countries (Adkins

2006). However, the

French Revolution was not only a crucial event considered in the context of

Western history, but was also, perhaps the single most crucial influence on

intellectual, philosophical, and political life in many European nations in the

nineteenth century. The revolution was certainly not caused by the effects of

climatic cooling alone, but these climatic effects surely had an important

influence along with many other drivers.

In

its early stages the French Revolution portrayed itself as a triumph of the

forces of reason over those of superstition and privilege, and as such it was

welcomed not only by both radicals and by many liberals as well, with its

declared emphasis on "Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity". As the

revolution slowly descended into the madness of the Reign of Terror, however,

many who had initially greeted it with enthusiasm had second thoughts. Among the

many subsequent events that can be traced to the French Revolution are much European

scientific progress and the

Napoleonic Wars.

Click

here to jump back to the list of contents.